We need to have a serious discussion about what we call a “good college.” Having recently gone through the college application process with my oldest child—and now starting it again with my youngest—I’ve been thinking a lot about choosing a college and what makes a good college. We need to reconsider the better define what and who gets to define a best, top, good, or (god-forbid) elite colleges. Who can we trust to tell us which colleges are best? How should a family define what makes a college “best”? Is it the educational experience, rankings, social life, brand/reputation, cost, or something else entirely?

Let’s explore this …

First, let’s get on the same page about some basic college data. Most people when talking about college mean non-profit residential institutions that award at least bachelor’s degrees and admit first-year students.

This means there are (or were when I gathered this data in 2024) a total of 3,768 colleges and only 1,595 are not open admission (the rest admit all applicants). So there are about 1,600 colleges in the country. All with different missions, academic focuses, sizes, etc. Good/best/top is probably a terrible way to try to describe this wide array of institutions. Trying to measure what’s a “good” college is like trying to find the best restaurant in New York or prettiest beach in the U.S. Virgin Islands (this list is insane … the only right answer is Coki Point).

Next, there is no independent agency or oversight body that evaluates higher education institutions. So, of course, private businesses stepped in to fill the void. Since the 1980s, magazines, guidebooks, test prep companies, and others have selected the factors they believe define a ‘good college’ and published rankings they claim are objective and scientific. Some non-profit organizations (think tanks, research institutes, etc) have tried to reframe the conversation in recent years, with uneven success.

Since there is no uniform, unbiased evaluator, we, the public, must answer the question individually using whatever resources we can find. So keeping that in mind, I’m going to look at some of the ways that colleges have been evaluate and then make recommendations for things you can do to better choose a college for your family.

Rankings

I’ve written a lot about what I don’t like about rankings, so I won’t rehash that here other than to say: make sure you look at the methodology of any ranking before you use it. Look at the factors in US News rankings, are these the things you’d look for in a college? Do you want to go to a college that other college presidents (who likely never visited) think is good? Do you care about how much the faculty at your child’s college are paid? These things might be tertiary or quaternary factors in quality; they are certainly not primary.

If I’m going to consider a ranking, I only use it in the broadest way: grouping schools into 3 – 5 categories. Rankings tell you “someone thought this place was good.” That’s enough to add that college to my initial list for more research. I don’t care whether the site was a magazine or a test prep company, they all just hired someone to filter their opinion through math, to gather various data, and make evaluations. But any school that makes someone’s best list is worth thinking about.

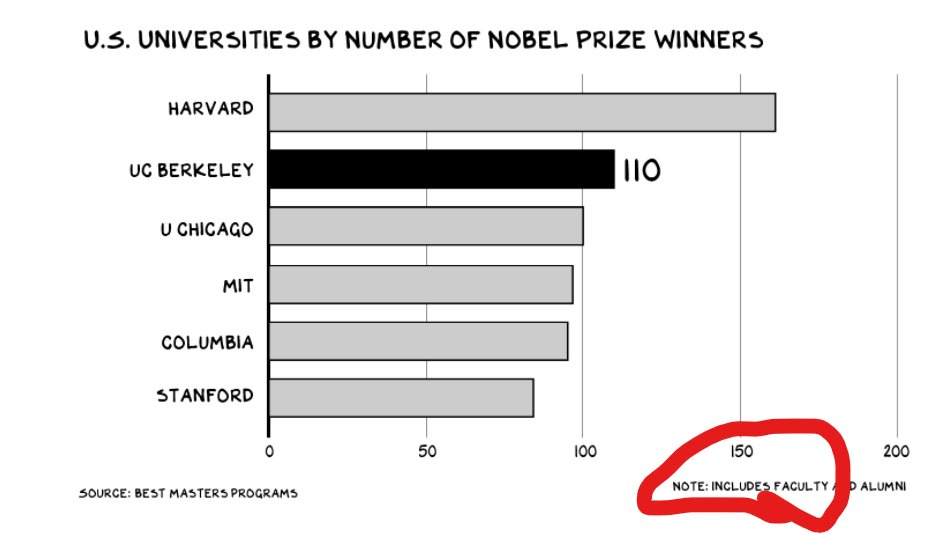

Another quick example of weird/deceptive rankings. This ranking list which universities had the most Nobel prize winners but check the note at the bottom. It includes the winners the school hired who were likely trained elsewhere! Also compare the number of winners at a school that is 389 years old to one that is 135 years old without at least mentioning that is really bad methodology.

Recently, I helped a family compile an initial list of colleges for their child to study film-making. I googled “top film programs,” “best film production colleges” and a few other variations. From these searches, I looked at any half-reputable site and added all the schools they called best to a spreadsheet. There was a lot of overlap but this got me a list of about 60 schools all of which had film programs that were good by one definition or another. This gave a great starting point for a college list and is the only way I recommend using rankings. I think about college rankings like I think about restaurant reviews: They are other people’s opinions not objective truth, and they are often based on things I don’t care about.

I’ve been to too many highly ranked restaurants that were terrible to trust ratings fully. Always be cautious of rankings and crowd-sourcing because so many are just terrible. Like this one:

With these cautions in mind, I like ratings (groupings into categories) and well-defined evaluations over vague “best,” “top,” or “ivy” lists that do not communicate what they are measuring. Some good ones are Best College For Your Money (because it’s clear that money is the primary consideration) or Top Feeder of Black Student to Law School (because that clearly tells me that if I’m interested in law that resources and programs exists at these places). If I’m concerned about my child’s potential to earn more than I have I’ll look for colleges with strong social mobility scores. Here are a few rankings I like: Ed Reform Now, Washington Monthly, CollegeNet and ThirdWay.

Finally, this article on Northern Arizona University is worth reading:

Selectivity

Lot’s of websites and rankings like to use selectivity as a measure of the quality, but it’s not, it’s a measure of popularity. Selectivity is just a matter of math. If a college has 1000 spots in its first year class and receives 2,000 application, is it a better college than one that has 1,000 spots and receives 10,000 applications? What if College A is in Brunswick, Maine and College B is in Los Angeles? I’d bet the greater application volume is driven as much by location as by anything else. So all college data needs to be evaluated with thoughtfulness and nuance.

Also the selectivity conversation is used by business to exaggerate the drama around college admissions by making it appear that all colleges are highly rejectiveTM, but of course that’s not true. Here is the data on selectivity:

If you only focus on selectivity as the marker of good, how many colleges are you restricting your list to? Also if you focus on popularity/selectivity as a measure of the quality you are essentially crowd-sourcing. Crowd-sourcing might not be a terrible thing for choosing a pair of jeans, but it is terrible for making an investment of tens of thousands dollars and 4 years of life. Here’s a closer look at some selectivity data:

| Yield Rate (Percent of accepted students who enroll) | Admissions Rate | |

Case Western Reserve University | 14% | 29% |

| Lehigh University | 28% | 29% |

| The University of Texas at Austin | 49% | 29% |

| Methodist College | 100% | 31% |

| Bryn Mawr College | 35% | 31% |

| Tuskegee University | 23% | 31% |

| Kenyon College | 18% | 31% |

| Bucknell University | 29% | 32% |

| William & Mary | 28% | 33% |

| Berea College | 61% | 33% |

| Davis College | 100% | 33% |

The colleges above all have very similar admissions/selectivity rates. If admissions rate is a good measure of quality than Bryn Mawr and Methodist College are essentially the same quality institutions. Further, since yield rate is the percent of admitted students who choose to enroll (another popularity marker), an institution with a yield rate of 100% must be better than one with a rate of 18%, right? Or maybe none of these numbers are enough to tell you the real story of popularity, and definitely not anything about educational quality. They are an indication of something more than just popularity but what is hard to know.

Outcomes (earnings and job placement)

The way I remember it from high school (back in the last century), college was of a place where you sat with the scholar and learned for the sake of learning. That learning would eventually benefit you in your career but a career wasn’t the object of college. It seems that of late the definition of a good college is shifting from “provides a good education” to “provides top 10% career earnings” and that makes me sad. To reduce education to a salary is 1. reductive (though practical) and 2. ignores all the ways in which American nepotism, capitalism, and cliquishness effect hiring. But that’s another discussion.

To find a good college (for you), when you look at outcomes make sure you look at inputs as well as outputs. Colleges are often given credit for the outcomes of students who were already destined to be successful (because of genius, parental connections, or other things). Consider the unnamed colleges below. Are they “good colleges” or country clubs? Does the fact that they recruit and enroll students from the wealthiest families make it more or less likely that the college has little to do with the success and earnings of their students.

So I don’t say all this to suggests the colleges above are bad, but perhaps they aren’t the best overall (I could easily be convince that CalTech is best in thermonuclearsomethingsomething linear calculus engineering studies but I’m sure their theater department sucks) so much as the wealthiest.

But college outcomes are a consideration.

When the Chetty Group was good they investigated wealth inequality in higher education, showing clearly that many highly rejective colleges overenroll rich kids. We can look at median earnings of students who got aid (so not counting those who had private loans or paid cash), and what percent of a college’s students did the college actually help (as in starting poor and moving up). This evaluation avoids giving credit to colleges that simply help the rich stay rich.

So how do you find the best? I suggest that you take all data with a grain of salt. And look at what the data might suggest about the college. If I’m a low income student, will that school help me become better off? Will it have the resources I need or will they make me clean up after my classmates to pay my bills.

Outcome measures like salaries post-graduation are interesting data, but by themselves don’t tell the full story. So as you’re considering schools, make sure to think about all numbers in their greater context. Below is a screenshot from the Third Way Economic Mobility Index, which shows not just more granular salary data but how many Pell Grant students the college admitted (which is a proxy for low income students and helps you understand the population of the college, the average national Pell percent is about 30%).

Graduation Rate

One of the worst numbers that often get thrown around is graduation rate. Grad rates might hide more than they reveal about the quality of an institution. Graduation rates often reflect whether the college was willing to take even mild risks in admissions. A college that only admits wealthy students with 4.0 GPAs is of course going to have a high graduate rate. A public college with a mandate to admit all qualified students is going to have a lower graduation rate because some of those admitted will be too poor to pay for a second year or will have trouble in calculus class and can’t afford a tutor. If a college—or any institution claiming to serve the public good—takes no risks to help those most in need, what will it accomplish besides calcifying the status quo?

Graduation rate are also calculated in a way that penalizes universities when students transfer. When I look at grad rate I make sure to look at transfer rate or to look up the withdrawal rate (which tracks the students who started at that school but didn’t continue anywhere at all).

Check out this slide, if you just look at the graduation rate of UMass Boston (51%) it might seem like a university that is ineffective at helping almost half of its students. But the transfer rate is about 30%, which tells me that the institution acts as a starting point for many students who then go on to finish up at other 4 year colleges. That’s a successful place. Now a place with a 50% withdrawal rate would concern me a great deal.

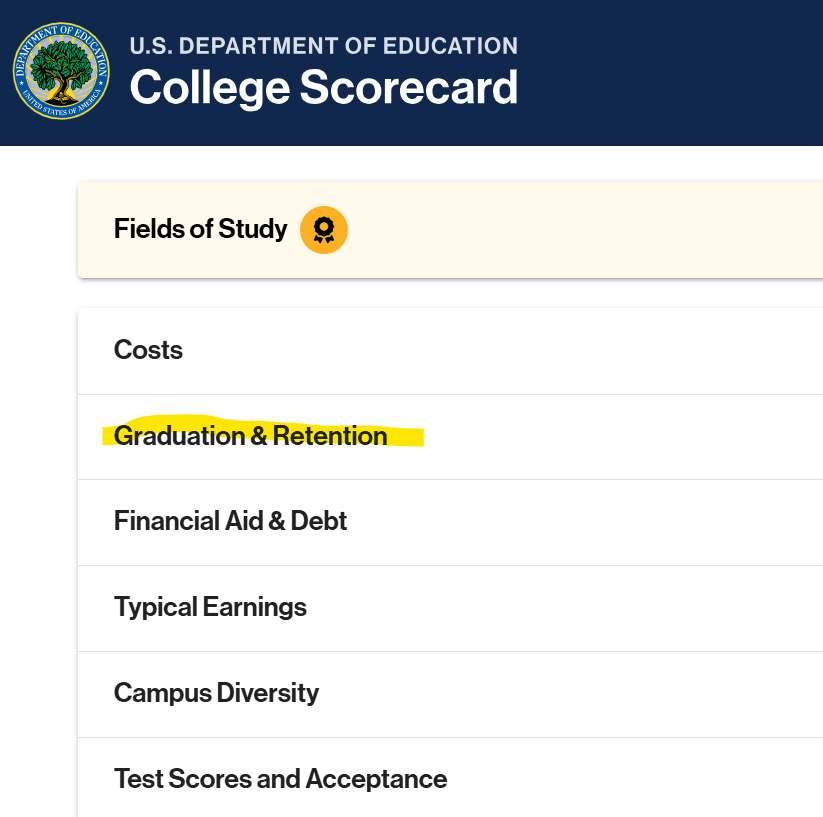

College Scorecard has both transfer rate and withdrawal rate (scroll to the bottom and go to the graduation and retention section). College Results Online has graduation rates by race (but doesn’t have withdrawal rates by race sadly).

So How Do You Find A Good School?

Finding a tall player is easier than finding a good player because of the specificity of the search. A better way to find the right college for your family might just be to drop the term good/best/top. Focus on what you want, finding “a mid-sized engineering focused school with a small gradate student population in the south and D1 sports” is far easier than finding a good school. Focus on what you want out of a college rather than, whether you can get into a particular college. Recognize that multiple colleges can offer similar opportunities and experiences. There are very few things that exist at only one college.

Ask big questions about college and the experience. Does your family value prestige above all else? Is your family most interested in colleges in blue states? Do you want a small college? Is cost the primary driver? Liberal arts college? Big sports school? Each of these factors will narrow the list of possible colleges to those that might be meet the requirements of the student. Almost none of these factors are captured in various rankings and best of lists.

What about the non-starters? Do you want to avoid colleges that consistently show up on lists of colleges that produce the greatest number of criminals? Are you interested in schools that have offices dedicated to prestigious awards like Rhodes? Maybe you want to look for institutions with strong relationships to particular industries? These are all factors you can investigate and that might be more important to your college search than admit rates and rankings. If you begin looking at these it will help you identify colleges that meet your family’s needs and wants.

Of course, given the inescapability of rankings, selectivity, and brand you might have to factor that in but don’t let it drive decisions and where you apply.

Here are some websites that might help your search:

- College Scorecard – Great for searching transfer rates, average debt, financial aid

- College Results Online – Lots of demographics on graduation rates

- Datausa.io – strong visualizations, good explanation of data, data is a little old (2022), shows average fin aid by family income over the past few years

- NYT Build Your Own Rankings – Let’s you shift the weight of some factors

- Loper.com – paid site/app, interesting search that hides names initially and encourages criteria driven search.

In the long run, A school is only good if it meets your family’s financial, ethical, and academic needs.

Other resources and recommended reading

- Challenging the “Good College” Myth – article

- Full List of Colleges That Offer Free Tuition Based on Income – Newsweek article

- Colleges that Change Lives – an association of colleges

Thank you for posting this. There’s so much to unpack philosophically here, along with helpful resources for students and families.

You give wise counsel when you advise investigating rankings’ methodology. Your point about there not being an unbiased source determining what is the “best” college may indicate a deeper issue, one that you touch upon in your article. First, there’s the obvious observation that what is best differs for different students. But there is a secondary issue here, too, that you allude to in your selectivity table- we lump all sorts of institutions with different aims and approaches under the label “college.” Yet, an institution geared toward giving students a step onto the ladder will look different than one whose students are attempting to climb to higher rungs. A school that is training via pre-professional programs will look different than one trying to provide a broad-based education built upon classical foundations of knowledge.

The section where you discuss how the idea of “best college” has shifted over time:

college was of a place where you sat with the scholar and learned for the sake of learning. That learning would eventually benefit you in your career but a career wasn’t the object of college. It seems that of late the definition of a good college is shifting from “provides a good education” to “provides top 10% career earnings” and that makes me sad,

is dismaying and makes me sad, too. It’s a set-up for failure: if 60%(BLS) of high school grads enroll in college, they aren’t all going to end up in the top 10% for career earnings, even if no one who doesn’t attend college is ever in that top 10%. The math just doesn’t work. It makes college begin to sound like Lake Wobegon, where “all the children are above average.”

Judging college quality by future income also falls into the all-too-common trap of reducing qualitative information (educational quality across a broad range of students and institution types) into something measurable and thus quantifiable, even if it is insufficient and potentially biased.

I think the societal swerve to reducing college quality to “provides $x earnings” primarily stems from how college sticker prices have significantly outpaced inflation for decades(leading to larger and larger gaps between sticker price and median family income). As a result, if a given college doesn’t lead to a high salary, the students end up in a financial abyss.

Yet your younger self’s thoughts of what qualifies as a good college remain spot on. Colleges should prepare their students to be thoughtful and engaged citizens with some applicable skills, so that students can zig to meet changing conditions and don’t regret having attended college. They should leave college and know more. They shouldn’t be drowning in debt nor living in poverty. They should be well-equipped to participate in cultural, societal, and governmental institutions if they wish to do so.

These qualities illustrate what students should possess if they have attended a “good” college, no matter their socioeconomic standing when they enrolled. So, when I look at your table of mystery colleges 1-10 based on income, I don’t learn anything. I do not judge colleges’ performance based on the income of families; I judge based on the experiences of current students, both in and outside the classrooms. If I were to judge based solely on family income, Berea could never be considered a good school. Yet, it does an extraordinary job of educating students while concurrently sitting at or near the top of social mobility rankings.

So, I return to your opening question: what constitutes a good college? Is it one where a student who starts poor ends up rich? That seems an overly narrow definition that would only be relevant to those who started poor. Or does a good college lead to a rich life in a more expansive, less pecuniary sense? Even when focused on dollars, think of the percentage increase in family income of someone who starts at the bottom of the wealth distribution and ends up at the 75th percentile! What does such a jump imply for a person’s quality of life? Where I live, in the not-so-distant past, that would have been the difference in whether a family had indoor plumbing.

Your piece is full of such astute and helpful observations that I hesitate to bring up the places where I disagree, but there are two places where I would attach some caveats.

First, I think faculty salaries are less tertiary than you believe. When faculty are paid less than at similar institutions, they are more likely to leave. Faculty departures can have a deleterious effect on students’ college experience, both within the classroom and in terms of mentorship and research opportunities. So, I do care about faculty salaries to the extent that they affect retention rates.

Second, Nobel winners. Of course, you’re correct that the faculty members may have been trained elsewhere, but the idea is that they conduct research within a community of scholars, and some communities are more likely to lead to Nobel prize-level research than others. In addition, current students may benefit from classroom and research opportunities from the Nobel prize winners on faculty.

Thank you again for integrating data and perspective into a discussion that is too often reduced to reductive lists.

LikeLike

Thanks for the comment. I thought about addressing some of these things but my post is probably already way longer than most people will read (its certainly longer than I intended to write)!

LikeLike

As is/was mine! But important things are worth the time.

LikeLike